What's

New

- Winners Gallery

- Katrina's Editorials

- Health and Fitness

- Special Offers

- Field Experts

-

Travelogs

-

July 2012

Aspen Summer -

February 2012

Ladies' Trip to India -

September 2011

Grazing Our Way through the “New Tuscany” -

Summer 2011

Biarritz, San Sebastian & more -

June 2011

Vietnam: Traditions and Transformations -

April 2011

Peru Spring Break -

April 2011

Ski & Sea Spring Break -

December 2010

Miami Art Basel -

September 2010

The East Side of Eden -

September 2010

Buenos Aires, Sao Paulo and Rio -

August 2010

Ionian Bliss -

August 2010

Buzz-worthy Berlin -

July 2010

Alaska Adventure -

April 2010

Springtime in New York -

February 2010

Aspen: Winter Wonderland -

January 2010

Australia: Home for the Holidays -

November 2009

New York: Dining, Theater & Art -

October 2009

London Art & Dining -

September 2009

Japan Journey -

June 2009

Peru Adventure

-

July 2012

- Newsletters

- Press

- MLS Signature Trip: Arctic Adventure

Travelogs

The East Side of Eden

Spotting wildlife in the rainforest takes patience and luck. Unlike an African safari, where animals roam out in the open and travel in herds, rainforest animals are stealthy and often solitary. During my rainforest adventures in Peru and Guyana, some days were rich with birds, monkeys and otters, and other days, not so much. It wasn’t until I visited Costa Rica that I saw wildlife in safari-like plentitude, seemingly everywhere I looked.

Though first-time visitors to Costa Rica usually head to the Arenal volcano and the Pacific Coast, we spent most our time in eastern portion of the country (we went in September, when it tends to rain in the central and western regions but is fairly dry on the Caribbean coast). Our first stop was Rancho Naturalista, a famous birding lodge in the Turrialba region. The lodge’s large veranda overlooked Turrialba Volcano and was hung with several hummingbird feeders – dozens of hummingbirds buzzed and zoomed, unafraid of us and diving cheekily at one another. On the lawn, bananas were strewn to attract motmots, tanagers and other tropical birds. It seemed a bit like cheating, relaxing on the veranda with coffee as we birdwatched at our leisure. But other birds, we had to work for. The local guide, Cali, took us on several hikes through the rainforest, pointing out vividly colored manakins and drab antbirds that were nearly invisible against the leaf-littered forest floor. We spotted an elusive sun bittern stalking along the river, and got a glimpse of the tiny snowcap hummingbird, indigenous to this area.

Next, we headed to Costa Rica’s Tortuguero National Park, the western Caribbean’s most important nesting site for green turtles. We stayed at Tortuga Lodge, located on a broad canal that parallels the Caribbean Sea – the park is threaded with canals, so everyone gets around by boat. The lodge itself is beautifully airy and luxurious without making you forget you’re in the jungle. We had lucked into a suite, which had a broad veranda, billowing drapes and brightly colored pillows – Latin America meets Arabian Nights.

We started our visit with a private boat tour of the canals. Our guide’s Caribbean accent had me stumped a few times (“Often I see a sloat in this tree.” A what? Oh, a sloth!) but he was fantastic at spotting wildlife. We saw a troop of lanky red spider monkeys, some black howler monkeys (one with a baby on her back), basilisk lizards, caiman, several types of heron, and a giant river otter napping in a hollow beneath the riverbank, who gazed at us indifferently before rolling over and snuggling back to sleep.

The lodge had arranged a turtle-watching experience for us that night at the primary nesting beach, 30 minutes or so by boat from the lodge. As we walked along the moonlit sand, we saw parallel marks, like tire tracks, leading from the lapping waves to the edge of the forest. Our guide, Fernando, led us up one set of tracks. Though I knew what we were looking for, I still gasped when his red flashlight landed on the sleepy-eyed face and enormous flippers of a green sea turtle, in the process of laying her eggs.

We crept around behind the turtle, which had dug a large pit in the sand beneath her lower body. Fernando reached down and moved her rear flippers aside. I was astonished – we been told not to use flash cameras or white flashlights, make loud noises, or in any other way disturb the turtles. But he explained that once the turtles begin to lay, they enter a sort of trance and don’t notice being touched.

Sea turtles don’t see the red spectrum of light the way we do, so Fernando was able to shine his light down onto the eggs. They were about the size and color of ping-pong balls, and dropped two at a time into the nest. When the turtle was through, she scooped sand onto the eggs with her rear flippers and packed it down, then tossed sand over the nest (and us) with broad swipes of her front flippers. At last, she began her long odyssey back to the sea. Making laborious breast-stroke motions, she pulled herself slowly down the beach – it took her at least 5 minutes to go 50 yards. When I think of the effort these female turtles go through, and the odds of their eggs hatching, and the baby turtles making it to the beach, and those babies living to adulthood, I appreciate how remarkable it is that these animals even exist.

After Tortuguero, we traveled south to the funky beach town of Puerto Viejo. Though Sept-Oct here means generally clear skies and calm waters, the high season is actually Nov-Apr, when the big waves come in, attracting crowds of surfers. We found it quiet and laid-back. Our boutique hotel, Le Chameleon, was contemporary and chic, with all-white décor accented with splashes of color that changed daily.

The next day we went for a snorkeling/wilderness tour in nearby Cahuita National Park. The snorkeling was decent (the highlight was a school of squid that moved in perfect formation), but the wilderness tour was beyond expectations. Our guide, Antonio, led us on a sandy path through the jungle – though only a mile or so long, the trail was chock-full of wildlife. We saw two- and three-toed sloths, capuchin monkeys, several black howler monkeys, and a bright yellow eyelash viper, coiled up in a tree like a ripening gourd. At one point, Antonio reached behind a log and pulled out a vine snake, whip-thin and very angry. It tried to bite him, but he only shrugged.

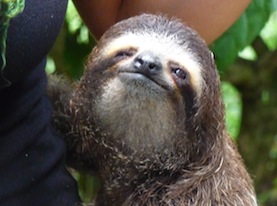

We decided to take it easy the following day, but this didn’t mean going without seeing animals – down the road from our hotel was the Jaguar Rescue Center, which takes in orphaned or injured animals and rehabilitates them when possible. They didn’t have any jaguars at the facility, but they did have a margay (a small, rare and beautiful jungle cat) as well as a variety of snakes, sloths, birds and monkeys. A volunteer staff member led us over to a hedge, from which several baby sloths hung like fruit. She wrapped a tawny, bright-eyed two-toed sloth in a blanket and plopped it into my husband’s arms, where it nestled contentedly; then she plucked a three-toed baby sloth off the shrubbery and held it on her hip – with its punk-rock-style eye band, it looked rather like a sleepy Grace Jones. Further down the hedge, a less social three-toed sloth was making a plodding break for freedom. The staffer grabbed it across the shoulder blades, keeping clear of its sharp claws and holding it up like a doll. It struck a spread-eagled pose, trying to look threatening. Three-toed sloths are slower than their toed-toed cousins, and easy prey despite being rather scrawny.

Within the center, a large cage held a dozen or so baby howler monkeys. To get them ready to return to nature, the staff allows them to interact with a local troop of wild howlers for a few hours each day. In the meantime, the babies were very used to humans, and we were allowed inside the pen. We were told that, though the monkeys were gentle, we should expect to be jumped on. Almost immediately, everyone in the group had a monkey on their shoulder or sitting on their head. It was a strange experience, but an utterly charming one.

After lunch at Bar Maxi, a wonderful beach shack in the village of Manzanillo, we moved to our second accommodations, Almonds and Corals Lodge. These huts, set on stilt platforms within deep forest and a short walk from the beach, were comfortably rustic and atmospheric, if a bit pricey. Though we never saw howler monkeys here, we heard them calling almost constantly – a mix of lion’s roar, bloodhound’s bay and bullfrog’s croak.

The next morning, we hired a boat for a dolphin-spotting cruise – a rare species of estuarine dolphins called tucuxis are often seen near Manzanillo, but not this day. It was the only wildlife disappointment of our trip, though the coastline was beautiful under the pink dawn sky. We made up for it later with a nighttime jungle hike at La Cieba Nature Reserve. Though they can be a bit spooky, night hikes are fascinating. Because you are moving slowly, being very cautious where you put your hands and feet, and your field of vision is largely limited to the circle of light from your headlamp, your attention is focused very closely on your surroundings. You aren’t likely to see many birds or mammals; instead, you notice strange plants, huge spiders, and colonies of ants on the march. Our guide was adept at catching frogs so we could study them – we got good looks at the red-eyed tree frog that is the emblem of Costa Rica. At the end of our tour, he led us to a large white sheet that had been hung near the lodge, with lights shining on it. The sheet was covered with a variety of flying insects, displaying elaborate patterns or clever camouflage. It reminded us how very alive the jungle is, and how diverse and superbly adapted its denizens are.

It’s no accident that Costa Rica is so rich in wildlife – 27% of its land is protected. For nature lovers like us, it was heaven. Costa Ricans have a ubiquitous expression, “pura vida,” which loosely translates to “life is good.” I couldn’t have said it better myself.

Chao,

Ellen

About Ellen Hall:

Ellen Hall is a writer by profession and an avid world traveler by inclination. Her first trip abroad was just after college, when she spent six weeks backpacking through Europe with her best friend. Since then, she travels whenever she gets the opportunity. Her trips usually focus on nature and history, and have included several return visits to Europe as well as Vietnam, Cambodia, Honduras, Peru, Japan, Costa Rica and Guyana. Some of her most memorable travel experiences include hiking the Inca trail, scuba diving with sharks in Honduras, volunteering at a vulture rescue center in Croatia, and paragliding in Slovenia.

Copyright 2013 MyLittleSwans, LLC. All rights reserved. My Little Swans, the logo and Share a world of experience are registered Trademarks of MyLittleSwans, LLC. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our Terms of Use and Privacy Policy.